There is enough testimony to convince you to start eating organic for better health. Stated simply, there are three simple reasons to choose organic over conventional foods:

- Nutrition is improved

- Toxic metal intake is reduced

- Pesticides intake is also reduced

For more facts and reasons, click here, the Organic Center.

Resolve to go ORGANIC IN 2015!

Simple Grocery Shopping Guidelines

When going grocery shopping, especially on a budget, consider the following guidelines:

- The first change to make is to buy ORGANIC BUTTER. The highest concentration of pesticides is found in non-organic butter. So, if you can only buy one organic item, it should be ORGANIC BUTTER.

- The second change to make is to buy ORGANIC MEATS. Non-organic meats have a higher concentration of pesticides than fruits and vegetables although not as much as non-organic butter.

- ORGANIC & FREE-RANGE EGGS are best. Free-range eggs are better than conventional, including just organic. Of the four types, ORGANIC & FREE-RANGE EGGS are less vulnerable to contamination due to structured housing enclosures. In addition, the organic feed is free of toxic pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides as well as not containing any genetically-modified organism.

- LOCALLY-GROWN ORGANICS are the best fruits and vegetables to buy. In fact, conventional fruits and vegetables grown locally are better than store bought. The latter gets transported in containers that contain toxins out gassing in transit and can contaminate the containers themselves, such as dichlorobenzene, not to mention adjacent boxes and cartons.

- Contrary to conventional thinking, use SOY PRODUCTS SPARINGLY. Even though most soybeans are genetically modified, they contain one of the highest levels of pesticide contamination of all foods!

- For product code information, click here.

The following article is reprinted from the NATIONAL RESOURCE DEFENSE COUNCIL on “Good Food Essentials: Shop Wisely, Cook Simply, Eat Well”

“How we eat determines to a considerable extent how the world is used,” writes Wendell Berry in What are People For? You want to eat right, and to feed your family foods that are both nutritious and good for the planet, but get so confused with all you read and hear in the news. Which is better–local or organic–or is that a false choice? Should we stop eating fish, too contaminated? What about beef, is any good for you?

Is it even possible that a healthier diet is also better for the planet? The answer of course to this question is a resounding “yes.” The food that is healthiest for you–fresh and whole, rich in variety, unprocessed, high in nutrients not empty calories–is also the healthiest for the earth, produced using methods that strive to be sustainable, meaning they aim to maintain and enhance our vital natural resources–water, energy, air, soil, land, biodiversity–upon which food production and life ultimately depends. Conversely, the foods that are highest in fat and require the most pesticides and fertilizers to produce are also the most energy-intensive and producing them takes the greatest toll on the planet.

It may seem an impossible task to turn around the American diet, and with it the way we produce food, but it’s not. Consumers have a lot of leverage in the marketplace, just look at how sales of organic products have grown, trans-fats have been squeezed out of cookies and crackers and even WalMart is sourcing more items locally. What makes it all possible though is that eating well is not so hard to do, and is easier on your wallet, and far more pleasing to the palate than the way we eat now. Follow these nine simple steps, applying them when you shop each week and prepare dinner each night. Use the many delicious recipes at NRDC’s Smarter Living as your inspiration and guide.

1. Vary your proteins.

Shifting your daily intake away from the “least-efficient” proteins – beef – to the “more-efficient” ones–chicken, fish, or better still grains, legumes, nuts, etc.–not only will be better for health but also will reduce pressure on the earth’s land and water resources.

credit: USDA

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 2007 the average American ate 90.64 pounds of beef a year, or a McDonald’s Quarter Pounder every day. This daily intake of red meat not only exceeds the dietary recommendations (no more than 2.5 oz. red meat per day, 17 oz. per week) of the Scientific Advisory Commission on Nutrition, the advisors to the federal guidelines, it also puts a lot of stress on the natural systems upon which life on this planet depends.

For one, agriculture contributes about 30 percent of all global GHG emissions, with beef alone contributing between 14 and 22 percent of the CO2 the world produces every year. According to the FAO, a quarter pound of ground beef releases four times as much GHGs as are released in the production of the same amount of pork, 14 times as much as chicken, and 50 to 60 times as much as fruits and vegetables. This is particularly true when the animals are raised in Confined Animal Feedlot Operations (CAFOs) where they are fed on corn or soy beans, since these crops are particularly energy intensive. If all Americans eliminated just one quarter-pound serving of beef per week, the reduction in heat-trapping pollutant emissions would be equivalent to taking four to six million cars off the road.

Beef production is also more water and feed intensive. To produce a kg of beef requires 15,500 litres of water in contrast to 3,900 litres to produce 1 kg of chicken meat. At the same time, beef cattle converts feed much less efficiently than other protein sources. Only 5 percent of feed is converted in cattle to protein, as compared to poultry and carp (an herbivorous fish) which have conversion rates of 25 and 30 percent respectively.

Check out Smarter Living’s Label Lookup when shopping for and its many great recipes to prepare your daily proteins right, whether they’re part of the main meal or an afternoon power snack. And be mindful of portion size, proteins should not dominate any meal.

2. When you do eat meat, eat grass-fed.

Animals that are grass-fed their entire life are healthier and their meat safer for you. A ruminant’s gut is normally a pH-neutral environment, best suited to a diet of foraging on cellulosic grasses. They are not well suited for a diet of corn and other grains, the primary fare of feedlot cattle. High in starch, low in roughage and a poor source of calcium and magnesium, corn upsets the cow’s stomach making it unnaturally acidic. This acidity is not only harmful to the cow, giving it a sort of bovine heartburn or worse making it very sick, it allows a whole range of parasites and diseases to gain a foothold, including the pathogenic E. coli 0157:H7 bacteria.

Grass-fed animals produce the right kind of fat. Many of us think of “corn-fed” beef as nutritionally superior, but it isn’t. A corn-fed cow does develop well-marbled flesh, but this is simply saturated fat that can’t be trimmed off. Grass-fed meat, on the other hand, is lower both in overall fat and in artery-clogging saturated fat. It also has the added advantage of providing more omega-3 fats. In addition to being higher in healthy omega-3s, meat from pastured cattle is also up to four times higher in vitamin E than meat from feedlot cattle, and much higher in conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a nutrient associated with lower heart disease and cancer risk that is lacking in our diets.

Grass-fed meat should be labeled. To know what the labels mean and which you can trust, use Smarter Living’s Label Lookup. If you are interested, here are more reasons for choosing grass-fed meat.

3. Eat a variety of fish, favoring those that are wild, lower on the food chain, and sustainably harvested.

The U.S. government just upped the recommended consumption of seafood to 8 oz. or more a week – more than twice what the average American eats – and 12 oz. for pregnant women. Eating fish can be a smart alternative to meat. It’s a lean protein with great health benefits. But seafood can be contaminated with high amounts of mercury or PCBs, causing ill health effects. And some varieties of seafood have been overfished or caught in ways that may cause lasting damage to our oceans and marine life.

Choose Your Seafood for Safety and Sustainability. Smaller fish that are lower on the food chain, herbivorous fish in particular, tend to be plentiful and better for health because they contain less mercury. Great small fish choices include squid, mackarel, tilapia, catfish, oysters, sardines, mussels, and barrimundi. Cook them up using our Smarter Living recipes.

Wild fish are almost always better for your health and the environment than farm-fished of the same variety, though interest in aquaculture is growing and there are some systems–above ground, closed loop, 100 percent recyclable–that don’t harm the environment or threaten wild species.

Knowing where fish is from and how it is caught is very important. American seafood isn’t perfect, but the U.S. variety of a particular type of fish is generally better than its imported counterpart because this country has stricter fishing and farming standards than do other parts of the world. You’re usually better off eating the local variety of a particular type of fish instead of its counterpart from across the country, unless that species has been depleted in local waters. Even out of season, the local fish that has been frozen is preferable, since fresh fish must be transported by air, the most energy-intensive method of shipping.

Read Here’s the Catch to learn about different methods of harvesting fish as there are more and less sustainable methods being used. Hook and line is a low-impact method of fishing that does no damage to the seafloor and lets fishermen throw back unwanted species, usually in time for them to survive. Intelligently designed traps are also good since they have doors that allow young fish to escape.

4. Eat first from your food shed.

On average, our food travels from 1500 to 2500 miles on its way to your plate, via transportation that guzzles gas and spews toxic emissions along the way, so if you have the option get as much as you can from local farmers markets and farm stands. The Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University, a premier think tank researching the impact of “food miles,” contends that local foods tend to be picked closer to peak ripeness and are less likely to be treated with the post-harvest chemicals used to prevent spoilage when produce is to be shipped.

Chefs have long favored local foods because they taste better and help keep regional culinary traditions alive. Both chefs and consumers can more easily contact–and even visit–local farms to see how the food is produced. Finally, when you support farms financially, you save them from the developer’s bulldozer, an all-too-common fate these days.

Note, too, that relying on locally produced foods means eating in sync with the seasons, a diet that includes root vegetables and preserved produce during cold weather. Use NRDC’s Eat Local widget to find out what’s in season and where the farmers market are near you. And follow the links to great recipes made with the seasonal foods you buy.

5. Eat organic produce where it counts the most.

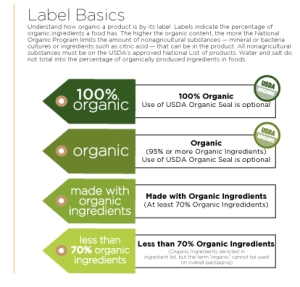

In 2002 the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) issued the first national organic standards and provided a product seal identifying and verifying food grown on “certified organic” farms. The standards set out the methods, practices, and substances used in producing and handling crops, livestock, and processed agricultural products. No synthetic pesticides may be used on crops unless they are on a list of approved substances. Similarly, to be certified organic, animals must be fed 100 percent certified organic feed, and cannot be treated with hormones or antibiotics.

There are clear health benefits to these rules. According to the National Academy of Sciences, more than 80 percent of the most commonly used pesticides have been classified as potentially carcinogenic, and many have been linked to increased risk of birth defects and human reproductive problems. Infants and children are particularly vulnerable to pesticides’ harmful effects, which is especially worrisome given that some 20 million youngsters age five and under in the U.S. consume an average of eight pesticides in food daily. All that said, organic food is simply not always available or affordable. So buy organic where it counts the most as when the conventional variety is known to contain high levels of pesticides.

6. Eat whole foods.

What’s a whole food? Whole foods of vegetable origin include fresh vegetables and fruits; whole grains (millet, brown rice, oats, rye, whole wheat, buckwheat, quinoa, cornmeal); beans and legumes (lentils, chick peas, kidney beans, etc); nuts and seeds. Whole foods of animal origin include eggs, small whole fish, seafood (shrimp, lobster, soft shell crabs), and small fowl.

Why is a whole food, say a whole grain, better than a fragment of it, meaning the bran or the germ. According to researchers, whole grains give better protection against chronic diseases than any of their component nutrients used as supplements. One of the major benefits of eating whole grains is that they slow down the digestive process, thereby allowing better absorption of the nutrients. Their fiber content also regulates blood sugar by slowing down the conversion of starches into glucose. Whole grains make favorable changes in the intestines, allowing healthful bacteria to keep disease-producing bacteria in check; they have strong anti-oxidant properties to help protect the body against free radicals, as well as phyto-estrogens and phytochemicals that break down carcinogenic substances.

Nutritionists suggest that a healthful daily diet would include at least 70 to 80 percent whole foods. Environmentally, the less processing a food item goes through en route from farm to table the fewer resources are used up.

7. “Bio-diversify” what you eat.

The Slow Food movement seeks to promote biodiversity in our food system by encouraging the cultivation and consumption of endangered food species, including heirloom vegetables, ancient grains and rare livestock breeds. Why? Because as Tim Lang, Professor of Food Policy, City University London, points out, “[A] real notion of sustainable diets must include multiple environmental factors, including biodiversity.”

While traditional agriculture depended on eighty thousand species of plants, industrial agriculture now provides most of the food on our planet from just fifteen to thirty species of cultivated plants. The current food system relies on just a few species of plants–primarily corn, wheat, rice–to provide nearly 60 percent of the calories the average American consumes.

The loss of diversity renders our food supply more vulnerable. Disease spreads quickly through a field planted with all the same crop, with the only defense against devastation being large amounts of pesticides. The rapid spread of the 2009 tomato blight was a case in point, demonstrating how in a highly centralized system – with lots of tomatoes grown in one place and distributed by a few large retailers – a “failure” can quickly multiply and the damage not so readily controlled. The recent spike in food-borne illnesses is another example of the problems associated with an overly consolidated food chain. E. coli’s been around for a long time; what’s new is how quickly and widely it spreads when there are only a few big meat producers.

“Healthy, natural systems” wrote Dan Barber in the New York Times, “abhor uniformity. We need, then, to look to a system of food and agriculture that values and mimics natural diversity. The five-acre monoculture of tomato plants next door might be local, but it’s really no different from the 200-acre one across the country: both have sacrificed the ecological insurance that comes with biodiversity.”

8. Minimize waste.

According to OnEarth magazine, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that Americans waste 30 percent of all edible food produced, bought, and sold in this country, although it acknowledges that this figure is probably low. Recently, two separate groups of scientists, one at the University of Arizona and another at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), published estimates of 40 percent or more. Add up all the losses that occur throughout the food chain, the NIH researchers say, and Americans, on average, waste 1,400 calories a day per person, or about two full meals.

What’s the environmental impact of all that wasted food? Tallying all the resources required to grow the food that is lost as it journeys from farm to processor to plate and beyond, the consequences of our wastefulness are staggering: 25 percent of all freshwater and 4 percent of all oil consumed in this country are used to produce food that is never eaten. That’s not all. Based on Environmental Protection Agency data, the 30 million tons of cast off food rotting in landfills may be responsible for about one-tenth of all anthropogenic methane emissions.

Who is generating most of the waste? According to USDA statistics, in 1995, some 5.4 billion pounds of food were lost at the retail level, while 91 billion pounds were lost in America’s kitchens, restaurants, and institutional cafeterias. In other words, food-service and consumer loss make up 95 percent of all food waste, which means most of the responsibility falls on those who prepare the food we eat, whether it’s a homemade meal, a dinner at a sit-down restaurant, or the Egg McMuffin we gobble down during the car ride to work.

What to do? Consumers can do the most good by embracing the good old “Three Rs”: reduce, reuse, recycle. Reduce how much “take out” food you buy each week. Planning meals better, using leftovers creatively (turn them into lunch to take to work, in reusable containers, of course, a thermos if it’s hot, a mini-cooler if it’s cold), and making just enough will mean much less food wasted at your home.

Food recovery programs play an important role by collecting surplus food from supermarkets, dining halls, and restaurants and delivering it to food banks and homeless shelters, where it is badly needed. For apple cores, potato peels, and other inedible food scraps, there’s composting-at home and, in a handful of places, on the municipal level.

When shopping, “vote” with your dollars for companies selling food in recycled packaging. Buy foods in bulk and from bins. Bring back bags for re-use. Avoid plastic wrap, which may transfer harmful chemicals to food. Annually, Americans consume 189 billion beverages sold in glass, plastic and aluminum –that’s two per day per person. Reduce your share by buying frozen concentrates and making your own drinks in reusable containers.

9. Eat home-cooked meals you make from scratch.

Now here’s a truly radical idea–cook your own meals at home starting with fresh whole foods. Obviously, by buying your own whole foods, preferably organic, you have the utmost control over how the ingredients in your meals are “processed.” Cooked-from-scratch meals also tend to be less expensive and involve much less waste. And using our many recipes, they can be fast, easy and affordable. So, don’t be surprised if you actually come to enjoy cooking and prefer what you can make simply, quickly and more cheaply than ordering in or going out.–last revised 8/19/2011